This post is part 5 of a series on changing PhD programs, chronicling my transition from the Colorado School of Mines to whatever comes next!

- Being sent on my first airborne gravity survey

- Totally not glamorous, involved a lot of time on a laptop in a hotel in central California

- Completing PhD applications

- Which made me really miss the days where the only way to send your transcript was a hard copy by mail, because every school I applied to had some subtly different form they wanted for the transcripts, and most of those subtle differences were only discovered in a blind panic at the last minute

- The winter holidays

- In which various people close to me made it clear that I was to take a break, or else

- Starting an application for a NASA Earth and Space Sciences Fellowship, and ending up starting a business instead

- Those two are only loosely related, as it turns out

- 40 hours of training for a new volunteering position

- I'm not very good at this whole "taking a break" thing

- Visiting one school!

- Liked the school, not the 6 AM flight I had to take to get there...

So now that we're all caught up.... in my last post I stated I had narrowed things down to 4 schools, and then in a footnote you may or may not have read (or remembered), I hinted that that had gone down to 3 schools. Reason being, funding for studying in the UK is somewhat difficult if you're a student from the US. The professor in question seemed eager to have a student, and had really interesting research and the funding to do it. The catch being that this funding would not cover a US student... So, for me, that meant either a) doing a 3-year PhD abroad with no stipend to support living expenses or b) getting lucky with scholarships.

Regarding option a), going without funding for living expenses for a graduate degree in the sciences is very uncommon, at least for the Earth Sciences. I've heard of people doing it for a two year master's (while working part-time), or maybe while finishing up a PhD, but definitely not for a full PhD. So if a professor is suggesting that you work for them without funding.... be very, very cautious about that situation. In my case, I didn't feel like anything untoward was going on - the professor was very upfront about how the funding worked, and funding is often tricky where international students are concerned. Since the funding situation had been made clear to me, I decided to see what options I had to find funding on my own.

Option b) (finding scholarships) proved to be riskier than I felt comfortable with. It turns out there just weren't that many scholarships I was eligible for in my situation. The only way I could figure out how to do it was getting the Fulbright scholarship, which was a very small number of slots for only one year of funding, and then getting lucky enough to get a second scholarship geared towards women getting science graduate degrees. I realized I could very likely wind up in a situation where I could be left in the lurch funding-wise halfway through my degree.

Since I was pretty happy with my other three options, and the logistics of heading off to the UK were a bit daunting even without the funding debacle, I decided to leave my study-abroad ambitions for another phase of my life. Perhaps a post-doc someday...

While we're on the topic of funding, I mentioned going after a NASA Earth and Space Sciences Fellowship (NESSF). I eventually ended up not going through with this, for a few good reasons. The first reason, which had been bugging me from the start of the process, is that while the NESSF goes with the student who wins it, I still didn't know where I was going to end up for school. I was working with one professor on ideas, and after a while the thought that I might brainstorm with this professor, get the NESSF, and then go to a different school after all that, just didn't sit well with me. If there's one thing I've learned about myself in the past few years, it's that I really value being honest with people, and I also value my own flexibility. Doing the NESSF now meant going against one or both of those values.

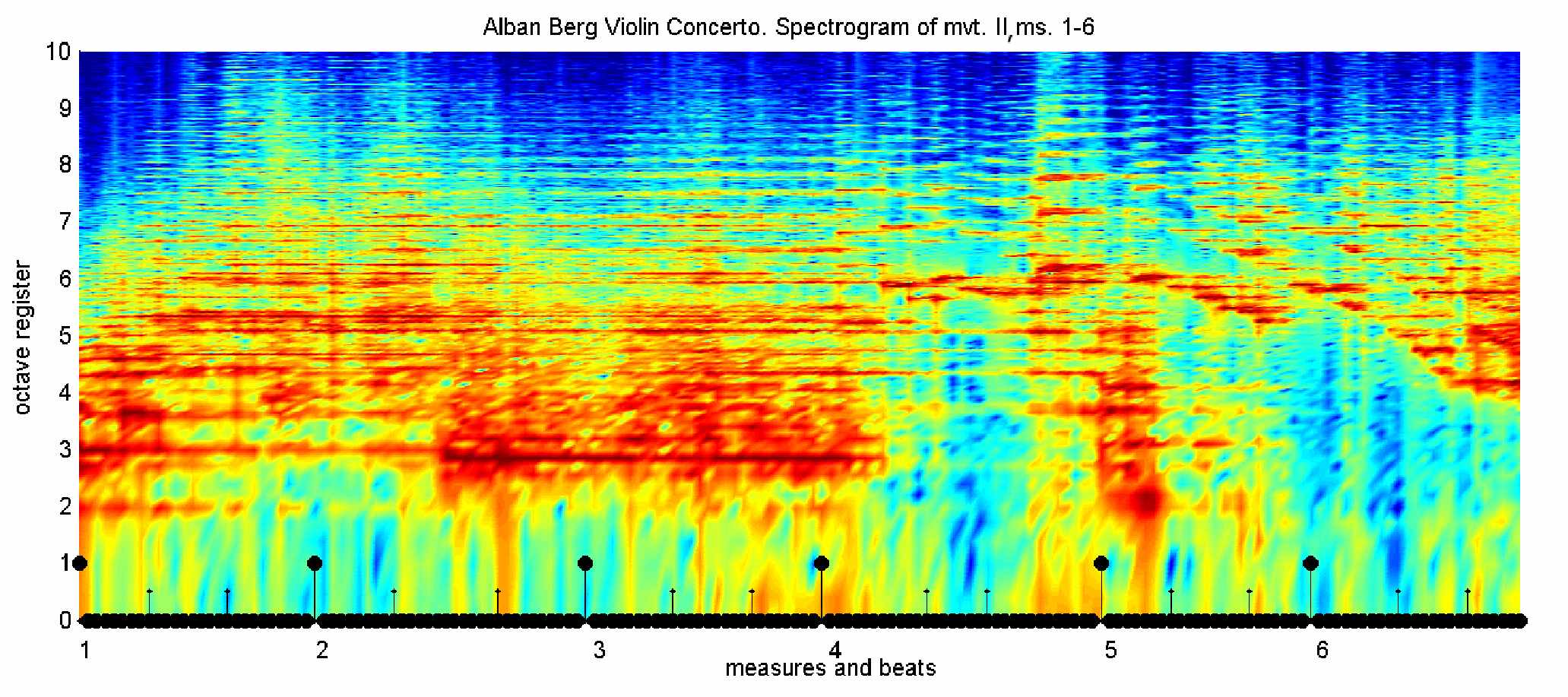

The second reason... I really don't know remote sensing well enough to write a proposal I would feel comfortable submitting! As part of trying to prepare the NESSF proposal, I looked over a few previously successful proposals. Reading through those proposals, and then trying to sit down and answer similar questions with my own proposal, I quickly realized I just didn't have the background to do a good proposal - right now. I know some people might read this and think "oh, this is just imposter syndrome! She's actually qualified and she's selling herself short." That's a fair point, as imposter syndrome is generally considered to be a A Thing for women in male-dominated fields*. However, as an argument in favor of my assessment of my background, I will point out that all of the successful proposals I read included one thing I most definitely did not have - preliminary results! I don't care how much confidence you have - you can't wish preliminary results into being! In the end, I decided that, rather than rush through a proposal I knew wouldn't be very good, I would much rather wait a year and submit a proposal I could be proud of. Not that this was an easy decision to come to - I really, really, do not like backing down on anything!

*For the counter-argument, read this very interesting article about how over-emphasis on imposter syndrome can end up distracting from the very real structural problems women in STEM fields face. But I digress.

So! Back to the thing I'm more excited about right now, which is figuring out how to be a volcanologist again! In the period between sending in my applications and starting to hear back from schools, I was pretty intensely anxious about getting in anywhere*. As with the first time I applied to a PhD program, I didn't have much of a backup plan if I didn't get in anywhere. I knew I could probably figure something out, but what, where, how soon? Would I just be perpetually stuck doing stuff I wasn't really all that crazy about?

*Work didn't help with this - dealing with a seemingly never-ending stream of gravity meters finding new and interesting ways to break on a daily basis hasn't exactly been conducive to functional insanity.

Thankfully, thankfully, the first offer of admission came in late January*, and for the first time in a long time I really, genuinely, started to feel hope about the future. Over the past month I've become slowly more and more convinced that I will be able to be a volcanologist again, something I wasn't really letting myself believe before. So if you see me starting off into the distance grinning like a crazy person... now you know why!

*So I guess the period of intense anxiety wasn't actually that long (since I sent in the last applications around the 5th of January) although it sure felt like it!

|

| I'm a happy volcano! This is a real photo of the lava lake on Pu`u O`o, the site of the current eruption on Kilauea's East Rift Zone. |

Last week I flew out to visit one of the schools I had applied to, and found out while I was there that they had accepted me - so now I have not one but two ways to be a volcanologist again! Even better, I genuinely liked what I saw and experienced of the town, the campus, the department, and most especially the professor. It really helped add to my feeling of happy anticipation about the future to know I genuinely liked at least one of the options.

I know it's not always an option for everyone looking at grad school, but if you can, I highly recommend visiting the campus before you make your decision. You're going to spend at least four years there - you want to make sure you'll like living there, for one thing! I also think it's important to meet people in person, to give all those little subconscious processes that we collectively refer to as our "gut" to work their magic. This is particularly important where the potential adviser is concerned, since so much of your academic success is dependent on this one person. It's also good to get a sense of your fellow students, too, as they will be your support system through all the ups and downs of grad school!

In two weeks, I'll be visiting the other two schools I applied to, and then I'll have to make my decision by April 15th. Based on what I've seen so far, I anticipate this being a very hard decision, for all the right reasons. It's a decision I'm looking forward to, because for the first time in a few years, rather than being a decision about avoiding further damage, this will be a decision about moving forward to improve my life.

Unless I decide to write another post about that final decision, I think this will be the last post in this series. I'd like to leave you with a nice pretty numbered list of important things to consider when you're either contemplating switching PhD programs or starting your search for the first time:

- It is OK to do a PhD. It is also OK to change your PhD if things aren't working. It's also OK to leave a PhD and start on a new path. Bottom line: it's your life, don't suffer - or avoid joy! - because someone else thinks you should.

- Know why you are doing what you are doing. Not so you can have a good excuse handy for well-meaning family and friends, but so that you can better understand what you need to look for.

- Pay attention to what gets you excited. This may mean deviating from what you've done for a while - and that's cool! If you already knew everything, there'd be no point in going for a PhD.

- PEOPLE ARE IMPORTANT. Talk to potential advisers - directly. Know who you'll be working with, and if you can work with them! Skype is great, in-person meetings even better, if possible. Also talk to current and former grad students!

- Funding is important! Generally speaking, don't go off and do research for someone who can't/won't pay you. In a science graduate degree, your work will support your adviser's work, and this needs to be compensated. Definitely for a 4+ year long PhD!

- PEOPLE ARE IMPORTANT. This is really really really important, so it's going on this list twice!

Thank you for reading my ramblings - I hope some of them were useful to some of you. If you're going through a similar transition, I wish you the best of luck - it can be pretty scary to jump ship, but I now finally believe that it can be worth it!

This is the (currently) final post in the "Leaving for Lava" series about changing PhD programs. Should you wish to peruse further, here are the previous posts in this series: